Marina Tabassum, the first South Asian architect to design London’s annual Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, has had a busy year. Her installation will be unveiled in Hyde Park on Friday, but she started work on it last summer, just as a popular revolution rocked her native Bangladesh. After a 15-year dictatorship crumbled in Bangladesh, Tabassum was put in charge of five of the country’s museums and established a new one dedicated to the recent uprising.

This role suits someone whose architectural practice has always sought to sustain Bangladesh’s regional materials, communities, and cultures. “There is a huge housing crisis in Dhaka,” Tabassum says. “People migrate to the city because there is a total lack of opportunity in other parts of the country.

It’s not a choice, it’s a necessity.” Typically, developers build multistorey concrete apartment buildings on individual plots, profiting enormously. Tabassum, however, prefers to work with locally abundant materials such as wood, brick, and mud. Through the Foundation for Architecture and Community Equity (Face), which she founded in 2018, Tabassum designs low-cost modular housing units for people living on islands in Bangladesh’s low-lying delta or on rivers.

These islands flood regularly and frequently disappear altogether, but local communities depend on them for their livelihoods and homes. “There are houses on the islands which have survived generations but have moved about 15 times,” she says. Tabassum designed a model house called the Khudi Bari for island-dwellers.

These easily assembled houses are built under the supervision of a carpenter appointed by Face, working to Tabassum’s plan.

Unveiling Bangladesh’s cultural identity

“It’s just a structure with two levels that is strong enough to withstand thunderstorms and water pressure when it floods,” she says.

“They can open the façade of the lower floor so the water can pass through.”

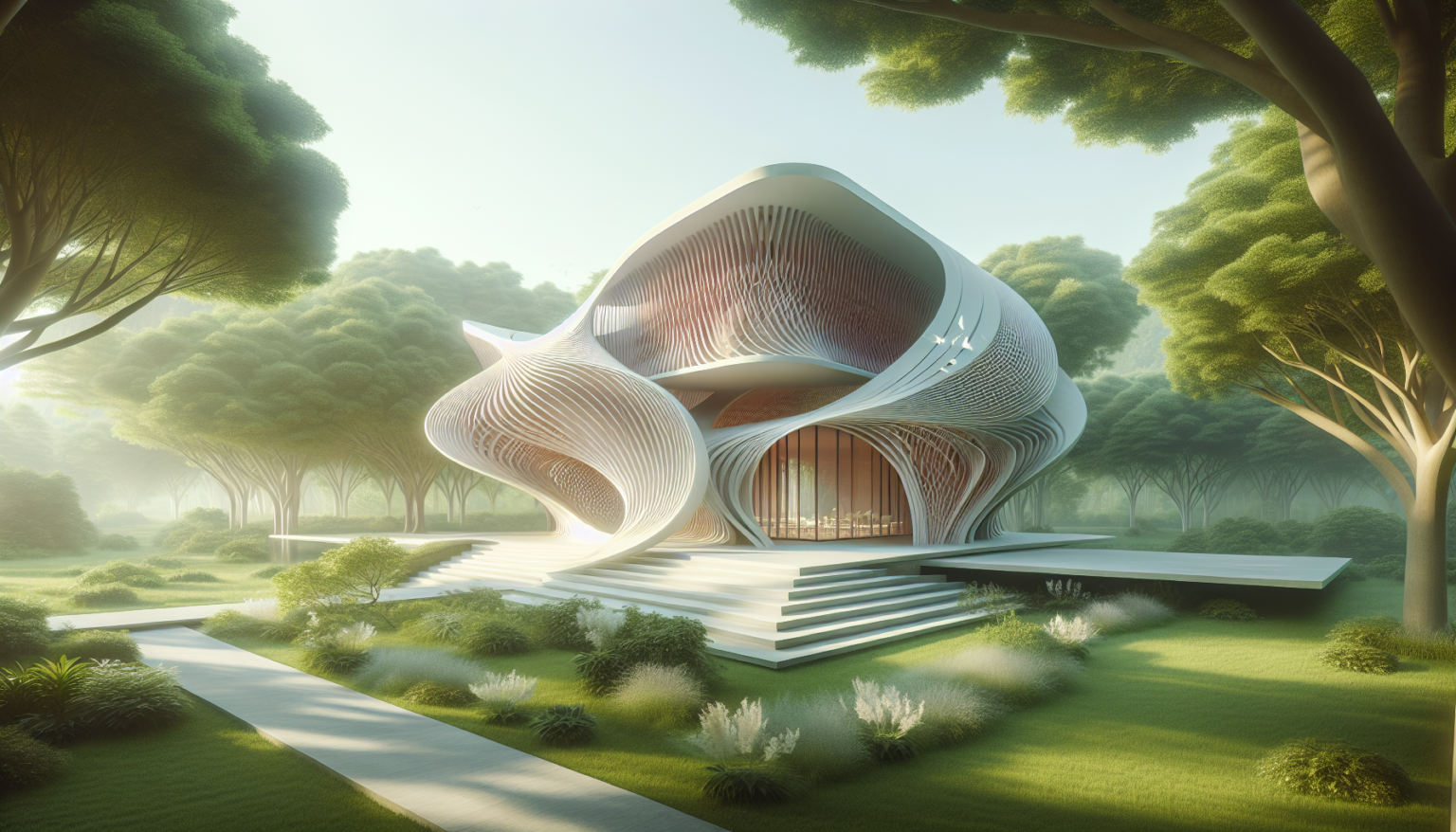

Tabassum’s Serpentine Pavilion builds on similar principles. It is inspired by tent-like structures, known as shamianas, made of patterned fabric stretched over wooden frames, used throughout South Asia for events like weddings and religious festivals. Their temporality resonates deeply with her.

“Throughout the subcontinent, people’s dwellings are made of fragile materials sourced from nature, needing frequent renewal,” she explains. She prioritizes the experience inside the structure, capturing light that is quite translucent. Much of the culture Tabassum is preserving as chairperson of the governing body of Bangladesh’s National Museum is characterized by impermanence.

For example, Bangladesh’s rich heritage of folk art was essential to 20th-century artists like Quamrul Hasan and Zainul Abedin, central figures in Bangladeshi modern art. Her biggest challenge now is getting these and many other fragile and valuable artifacts in Bangladeshi state collections properly catalogued and curated. “The museums have such rich collections, but 90% is kept in reserves and not seen by the public,” she says.

Tabassum is determined to change this. “It’s our cultural heritage, our identity—we have a duty to preserve it.” She faces a tight budget and slow-moving bureaucracy. For an architect who values impact, this may be her most critical task yet.